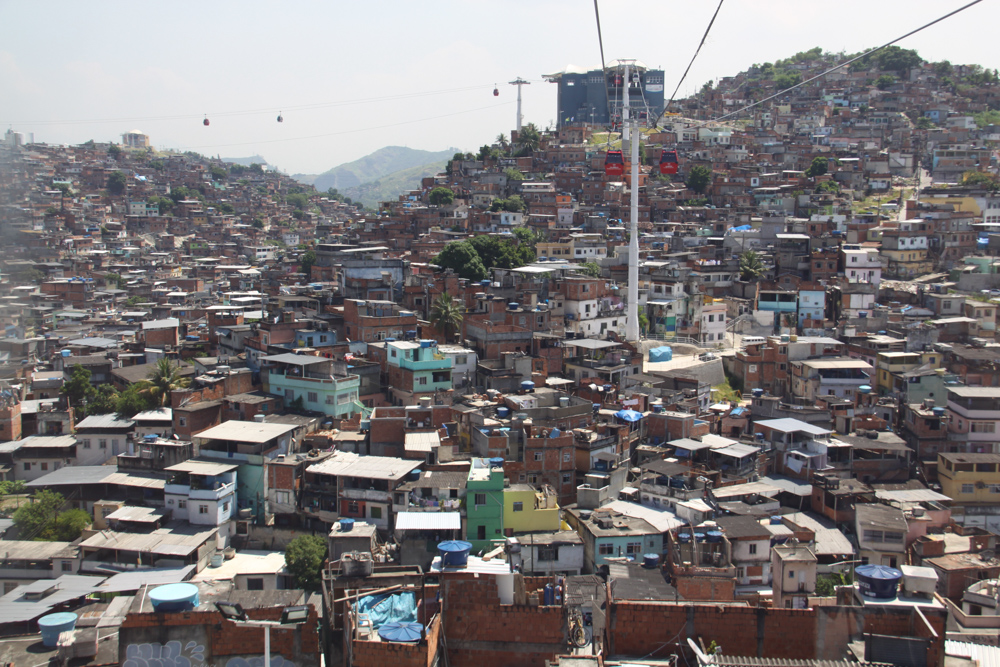

There are two sides to Rio de Janeiro. The part that you can go to, and the part that you can’t. Of course you can walk the wide boulevards of Copacabana or Ipanema, or maybe the nice shopping malls, but there is a part of Rio that everyone see’s that you can’t go. The hillside slums, known as favelas that make up a huge part of the city. The cops can’t go there. The tourists can’t go there. The government can’t go there. I was always infatuated by this part of Rio and knew that I had to go there. My first tentative steps to exploring the favelas was with a public tour guide that took groups to Rocinha, the largest and most well known favela in Rio. He had an agreement with the locals, and although it wasn’t required he strongly suggested we purchase a couple of drinks from the store in the slum and maybe a piece of art from the local artists that would meet our van. It was a taste of the favela, but a safe, sanitized taste, and I wanted to taste the bitter real Favela that I knew existed deeper inside. The favelas are controlled by gangs that primarily deal drugs. There are periods of time when a favela can be relatively calm, only to be suddenly interrupted by gang violence that can only be compared to war zones. The only hope is you don’t happen to be visiting when the shit hits the fan. In recent years the government has attempted to “pacify” some of the favelas, especially before the 2016 Olympics. Pacifying involves sending government troops armed to the teeth to expel whatever drug gang controls that favela and keeping an armed force to attempt to keep the peace. It was always ugly, and it rarely worked.

I knew a woman in Rio who worked in video production and she had occasionally worked in the favelas to shoot TV and commercial spots and made connections by paying for access to some of the no go areas. I asked if she could help, so she made some calls. Her contact told us to meet at the entrance to the favela at a certain time and he would show us around. When we met him (he spoke no English, so our friend was translating), he agreed to show us the favela, with one stipulation, we couldn’t take photos of any guns. I had no idea how prominent guns were in this neighborhood, but as soon as he jumped in the van and we started to drive up the hill I saw 3 kids standing on the sidewalk all holding automatic weapons. These kids were probably 9 years old or so. Holding machine guns. I begged our local friend through the translator to let me take this photo, I told him I wouldn’t show faces, and offered to pay him, but he reminded me of our agreement, no photos of guns, period. This was my first non-sanitized visit to a favela and I realized the reality of these neighborhoods. Living here was about survival.

I eventually became more comfortable visiting the favelas and started visiting some of them on my own. Once, another photographer and I visited a favela called Santa Marta, close to the center of Rio. As we started to wind our way up the maze of stairs and sidewalks we heard live Jazz music coming down the alley. We looked around to try and figure out where it was a coming from, and stumbled upon a little dark bar hidden in the concrete maze. The old guy playing the accordion gave us a smile, which made me feel better about barging their space with giant digital cameras. My friend thought quick, and bought a round of beers from the bar and put them in from of the old men. That seemed to give us permission to shoot photos of these amazing legends of the favela.

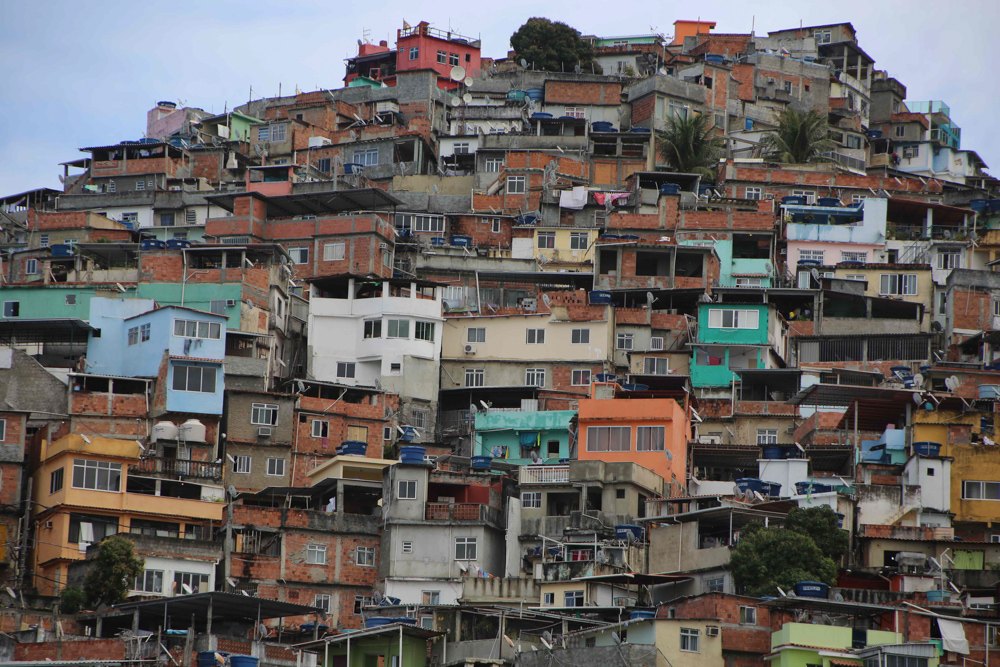

There are a few things that stand out in a favela. One is the ingenuity. Ramshackle construction on a sketchy hillside makes for some amazing feats of ghetto engineering. I see a set of workout weights fashioned from cement blocks, and kids flying a kite that is no more than a string with a piece of plastic attached. Another is the beauty. These hillside neighborhoods often have the best views in all of Rio, and with colors and paint a lot of residents have done their best to add some creative flair to their precarious living situation. One more thing that always stands out the first time you visit a favela is the literal insanity of the convoluted maze of power lines and millions of wires sprouting off every sketchy power pole. There’s no way this works. It’s interesting to speak to those inside the favela. Some speak broken English, and with some we speak through our friend who is translating. I learn that some favela residents leave the neighborhood to work in the “city” everyday, and there are some residents of the favela that literally never leave the slum.

These neighborhoods are a world of their own, they have their own rules and they have their own look. For better or worse, the favelas of Rio de Janeiro are unlike anywhere in the entire world.